The Doctor Will See You: Early medicine in Canada

(a talk by Maxime Chouinard)

We were privileged to hear Maxime Chouinard, the Curator of the Museum of Health Care housed in the Ann Baillie Building of Kingston General Hospital. Maxime explained that the impetus for the Museum came from Dr. James Low who began work on the project in 1988. In 1991 it opened to the public, and moved to Ann Baillie in 1999. The museum houses 40,000 objects including artifacts and documents dealing with doctors, nurses, and dental care.

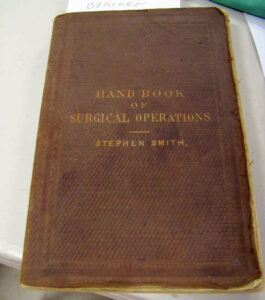

[right] Handbook of Surgical Procedure by Stephen Smith – a fairly slender volume

Mr. Chouinard entitled his talk “The Doctor Will See You: Early medicine in Canada”. He pointed out that as late as the early nineteenth century, there were very few regulations on the practice of medicine, and very little scientific knowledge. Most physicians followed the theories of Hippocrates and Galen, predominantly the Theory of Humours: that the body was controlled by four “humours” — blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile — and sickness arose when the humours got out of balance.

[left] Scarificator with blades raised

The most common way to deal with bad humours was bloodletting, either by application of leeches or by cutting into the patient’s flesh. Maxime displayed a bloodletting kit from the 1840s which included a “scarificator”: a metal device with several concealed blades which cut into the skin when triggered. He said there was no understanding of how much blood a body contained or how much could be removed at one time. George Washington’s death was in part due to repeated bloodlettings and subsequent infection.

Infection was a major problem because they did not sterilize equipment between uses. Another way to let out blood was by cupping: lighting a candle to create a vacuum inside a glass cup by burning the air inside. The cup then sucks the skin, creating an inflammation, but not a burn. The red-blue color of the skin which resulted was thought to be the bad humours being attracted to the surface.

Maxime also displayed a saw and knife from an amputation kit. Amputations were common, and surgeons prided themselves on how quickly they could amputate a limb (because there was no anaesthetic, and therefore the patient would suffer for a shorter time). Dr. James Douglas, a surgeon in Quebec City (and father of the James Douglas for whom one of Queen’s University’s libraries is named) claimed he could perform an amputation in under a minute.

[right] A trepan was used to open holes in the skull.

[right] A trepan was used to open holes in the skull.

By mid-19th century doctors came to understand the existence of disease-causing organisms. During the cholera epidemics of the 1830s, it was thought that heating air would disperse the disease and many cities set out barrels of burning tar in a vain effort to dispel the “vapours”. In contrast, in 1854 a Dr. John Snow observed that cases from another outbreak in London were all among people taking water from the same well, and it was realized that cholera was in fact water-borne.

[left] Maxime Chouinard demonstrates a dental molar extractor.

[left] Maxime Chouinard demonstrates a dental molar extractor.

Joseph Lister urged doctors to wash their hands between patients, and Louis Pasteur in 1859 disproved the theory of spontaneous generation of infection, demonstrating that organisms instead came from outside (air, water or contact) into a body. Scientific medicine came into being.

A most informative talk. We look forward to the next exhibit at the Museum of Health Care; a display on World War I Health Care will open next month.

All photos January 24 by Nancy Cutway