The Triumph of Villainy: The Loyalist Search for Honour in Defeat

(a talk by Dr. Tim Compeau)

November 27, 2021

The main presentation topic is not a happy or easy story to tell today. I’m going to talk to you about the Triumph of Villainy: The Loyalist Search for Honour in Defeat.

It’s a story about the Loyalist experience of losing their homes, and of losing their place in American Society. Their experience of dishonour was more than we usually understand.

It’s a story about the Loyalist experience of losing their homes, and of losing their place in American Society. Their experience of dishonour was more than we usually understand.

The Loyalist Search for Honour in Defeat

For the purposes of this talk today, when using the term ‘Loyalist’, I’m really talking about the educated ‘Loyalist Elite’ men and women who left behind detailed records of their thoughts in diaries and letters about their feelings of exile and resettlement after the American Revolution.” [Ed: These might be considered ‘Treasury Loyalists’ rather than UEL according to Dorchester’s Proclamation and UELAC.] These were people who thought of themselves as gentlemen. And my title today comes from a letter of Lieutenant Colonel John Peters of the Queen’s Loyal Rangers. He wrote in a letter to a friend that: “With the consciousness of having done right, I can look with disdain at the triumph of successful villainy.” Peters had once been a leading figure in the settlement around New York City. After the war, he and his family were in Britain, surviving on charity and a meager government stipend.

[Editor: Tim showed us this painting to illustrate the disparity between the publicized reception of the Loyalist by the British and the actual treatment of the Loyalist by the British Generals and officials. It is of John Eardley Wilmot, a Loyalist losses commissioner, and contains an inner painting titled Reception of the Loyalists in England. The full painting is by Benjamin West, painted in 1812, and the inner one does not exist fully elsewhere at all. With an idealized allegorical style, West’s ‘background image’ depicts ‘Britannia’ and West himself and his lady in the lower right welcoming the different peoples from America.]

[Editor: Tim showed us this painting to illustrate the disparity between the publicized reception of the Loyalist by the British and the actual treatment of the Loyalist by the British Generals and officials. It is of John Eardley Wilmot, a Loyalist losses commissioner, and contains an inner painting titled Reception of the Loyalists in England. The full painting is by Benjamin West, painted in 1812, and the inner one does not exist fully elsewhere at all. With an idealized allegorical style, West’s ‘background image’ depicts ‘Britannia’ and West himself and his lady in the lower right welcoming the different peoples from America.]

WILMOT Painting: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:JE_Wilmot_by_Benjamin_West.jpg

WEST Sketch Image source and explanation: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e0-f4eca3d9-e040-e00a18064a99; More info: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jYpaGNC08N0

From the point of view of people like John Peters, the ‘Reception’ was not welcoming, but instead he and many others felt insulted by the British authorities.

[Editor: The juxtaposition of the two images, with the larger painting of a ‘gatekeeper’ Loyalist Commissioner J.E.Wilmot, seems significant. The artist West remained silent on his politics (1) yet painted this background with Wilmot, who had stated (2) that he was perplexed by how different Loyalists acted upon their loyalism by joining or fleeing at such a wide range of dates. It makes one wonder if West realised that Wilmot did not fully understand the pressures felt by the Loyalists trying to balance ‘life and limb’ with their hopes for the future, and perhaps West wanted to present this conflict subtly.

When John Peters, above, was describing the triumph of successful villainy, he wasn’t just grief stricken and angry at the American rebels, he was deeply distressed by the treatment that he received and the poor management of the war by the Generals involved.

From the point of view of the Loyalists such as Peters and Joseph Galloway, a prominent Pennsylvania Loyalist, the British officers like William Howe and General John Burgoyne were responsible for losing the war and both later had the gall to refuse to acknowledge the Loyalist contributions and their suffering. These generals were even badmouthing the Loyalists in British high society. Peters, deeply hurt, argued that his allegiance to Britain was and always had been the honorable decision. Even though he lost everything, his family was destitute, and they’ve been driven from their homeland, he wrote,“I would do it all again if there was occasion.”

These Loyalist men, in their writings, pointed to British mismanagement and naivete, rather than pointing to any military superiority of the Rebel forces, such as those that Howe and Burgoyne suggested. And they clearly outlined the failure of Howe and Burgoyne to make better use of the Loyalists.

The situation was complex though. These writers could blame the British for their defeat all they wanted, but they relied on the potential testimony of these same British Generals to rebuild their lives. They needed the testimonial validation of their service by their superiors to prove their losses claims and yet at the same time they needed to restore their sense of honour.

The accounts in their letters demonstrate just how assertive and proud that the Loyalist elite were, while asserting that the Revolutionary War was lost and that the Loyalists were made homeless because of these foppish British generals who didn’t really know what they were doing.

The accounts in their letters demonstrate just how assertive and proud that the Loyalist elite were, while asserting that the Revolutionary War was lost and that the Loyalists were made homeless because of these foppish British generals who didn’t really know what they were doing.

Gananoque’s Colonel Joel Stone, a Connecticut Loyalist, and Honour Based Culture

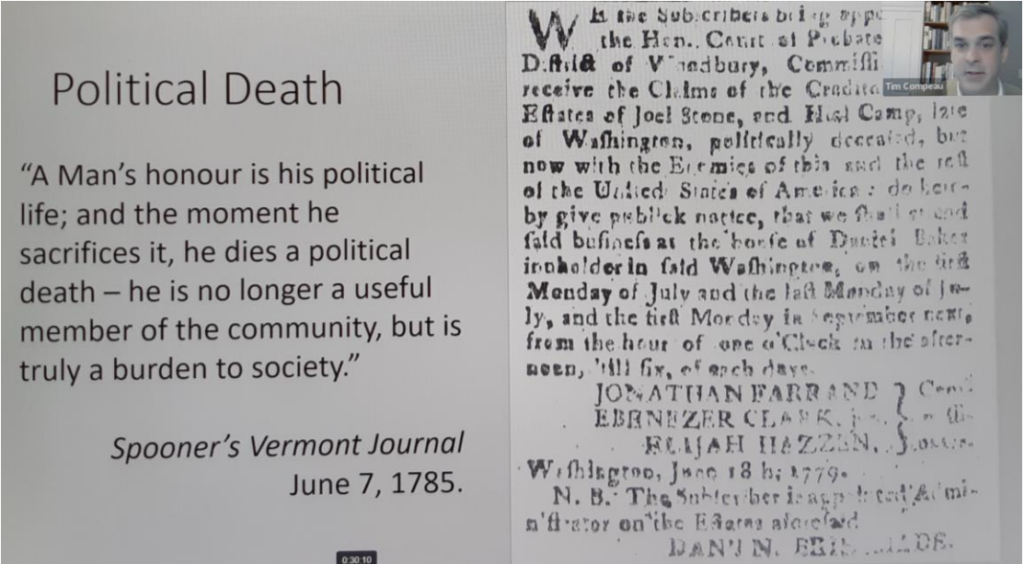

What we’re trying to do here is get into the mindset of people who lived in the 1770s. Honour meant something different than it does now. They and we want what’s best for our families, but they were operating in a very different culture and it’s important to understand their culture well enough to recognize how and why people behaved as they did. Their loss of honour as perpetrated by the Patriots was much deeper than we might initially think. Another man who lost honour was Joel Stone, and his situation and papers illustrated this ‘political death’.

Stone left a huge quantity of records, and we are very lucky to have them. He wrote in his claims to the British government that the Patriots rebels considered him unworthy to live. Rather than literal death, men who supported the King faced a legal and a social campaign that resulted in ‘political death’. The losses of property were deeply connected to the intense cultural and social impact of ‘political death’. Loyalists faced this campaign of humiliation and ostracism within an honour-based culture. Patriot attacks dishonoured the Loyalists and denied their place within their society. The importance of honour really can’t be overstated. This was a part of their identity and losing identity as a gentleman was a kind of death.

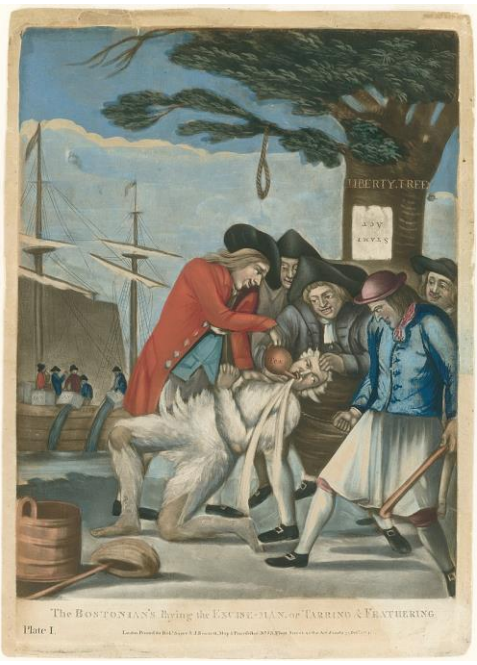

Relatively few Loyalists were actually tarred and feathered, but ‘cartoon’ images of that event showed the powerlessness they felt. These ‘politically dead’ Loyalists faced a frightening situation, could be attacked, vandalized and more by Patriots to thoroughly dishonour the Loyalist.

Relatively few Loyalists were actually tarred and feathered, but ‘cartoon’ images of that event showed the powerlessness they felt. These ‘politically dead’ Loyalists faced a frightening situation, could be attacked, vandalized and more by Patriots to thoroughly dishonour the Loyalist.

Having gone through this ‘political death’ at the hands of the Patriots while defending the British Empire, the Loyalist gentleman believed that he had served his sovereign, and earned his right to be treated with respect, to be welcomed into Britain and to be compensated, but such ‘Loyalists’ were quite surprised at the reception that they met in Britain. This was partly because these men largely grew up in an isolated New England, far from high society. They were very surprised at the nightlife of British culture and what they saw as debauchery.

Connecticut exile Loyalist and Yale Graduate Josh Chandler wrote to his friend in Massachusetts, of his astonishment at the decadent manners and customs he saw, referring to England as, “The great sink of corruption. … You could have no idea of the corruption of their debauchery, their luxury, their pride, their riches.” He realized it was ‘all plays, pubs’ and so on. Most of all, he was surprised at the significant support he found for the American cause, and it was very hurtful to him. It was clear the British were architects of their own defeat and of the ruin of the Loyalists. Seeing this, Loyalists became discouraged trying to get compensation.

They were torn between their resentment towards the British authorities who did not appreciate the extent of their suffering, and their need to regain honour. Several Loyalists wrote long accounts trying to explain what happened, and publishing pamphlets that stated their case.

Pamphlets, Histories, Compensation and Recovery from Political Death

Joseph Galloway wrote a guide-book that helped Loyalists navigate the bureaucracy to make their claim, while being respectful but also to hopefully get what was deserved. The ‘Elite Loyalists’ found the whole process insulting and tedious. In Britain’s defense, the process had to be done responsibly, but the Loyalists blamed Britain’s military leadership for the defeat.

Galloway and a writing partner wrote 25 different pamphlets. Some were against General Howe and his poor strategies, neglecting his duties, and ‘carousing’. Some were 160 pages long. Other pamphlets were by Lt. James Moody (a good candidate for a good movie about Loyalists) and Lt- Col. John Connolly.

Moody’s online Pamphlet: https://archive.org/details/cihm_56778/page/n7/mode/2up

General Howes’s responses basically denied all of Galloway’s accusations and put the blame on the Loyalists, saying that instead of Loyalists flocking to support the crown, they didn’t show up and many were only doing it for the money or they were spies. Howe asserted that Washington’s troops were well disciplined, well provisioned, and were good shots, providing ‘excuses’ for the losses.

General John Burgoyne was famous for leading the British into defeat at Saratoga in 1777. In their long dispute, Peters said: “Burgoyne is …foppish, he is lacking in character….” and didn’t listen to the Loyalists, driving the men into defeat. Burgoyne was well known in Britain, while no one knew John Peters, so it was a very lopsided dispute. What Peters needed was testimony and recognition from Burgoyne, his commander, to process his claim, but he never got it.

Peters responded to the allegations saying that, “…he, the General, knew that they [the Loyalists] had courage to leave their wives and their children and their friends and property and turn soldiers and go in the forefront of all his army to receive the first blows of the enemy and be guardians of each wing and the rear. And when in fact, the loyal provincials under his command were killed ten to one of the Royal Army…” Among other things, Burgoyne said that the Loyalists were really only fit for searching for cattle, ascertaining the roads and clearing brush.

Once Peters got to England and had been demoted by Haldimand to Captain, he appealed to Guy Carleton for help, but Peters died in 1788 without his compensation and recognition. Hence the ‘villainous treachery’ that he had already clearly described! Compensation for losses was often near thirty percent of a claim.

Loyalist honour was never fully restored with the compensation, but it was nonetheless a step on the road out of political death to political rebirth. The Claims Commission provided the Loyalists with the opportunity to compose narratives, which created a picture of an ideal, honourable Loyalist who served the Empire and became a martyr for the British Constitution and its notions of liberty. With the settlement of Loyalist New Brunswick, Upper Canada, Nova Scotia, and in the Bahamas and Jamaica and elsewhere, Loyalists had a sense that they had restored, at least in part, their place both as Patriarchs and Gentlemen, and their place in the imperial hierarchy, and this was an important step on the way to political rebirth.

Responses to two Questions:

Q: Were some Loyalists able to return to their former lives?

A: Yes. What we found was that many gentlemen had been part of networks and over the next 10 years, between 1783 till the early 90s, there was a process of reconciliation. Many were able to reconnect and resume their lives. It’s interesting that political death in dishonour was so intense for five or six years, and then people got over it.

Q: Were some compensated with a level of favoritism?

A: The system was not purely bureaucratic and purely meritocratic. It was often based on who you knew and how you can grease those wheels and get a bigger slice of the pie.

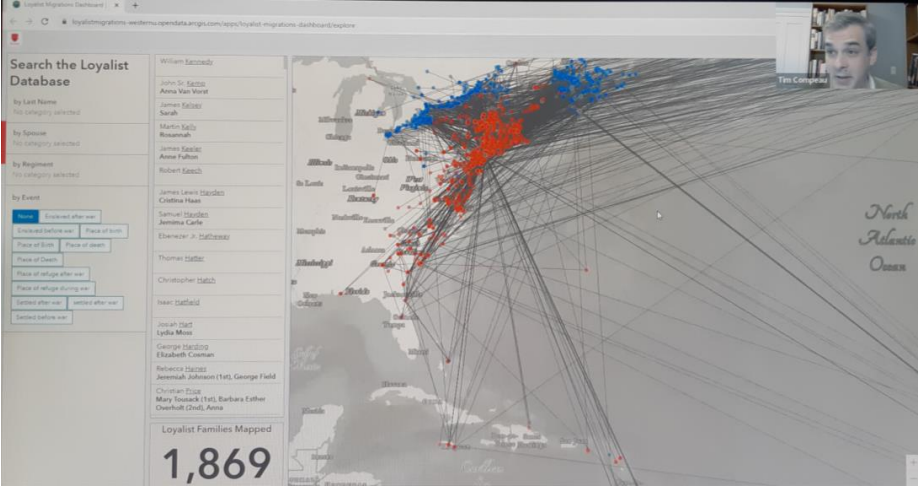

Loyalist Migrations is at: https://loyalistmigrations-westernu.opendata.arcgis.com/

Footnotes:

(1) https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1690&context=honors

(2) https://livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/3027558/1/200424173_Oct2018.pdf