In Search Of Captain Paul Trumpour UE: Cemetery Rambles

(by Mark Trumpour)

March 2020

In 2019 we reprinted an older article by Mark Trumpour about the Trumpour and other families. Mark has now written about more recent family explorations.

Paul Trumpour was one of the original settlers in Adolphustown, “Fourth Town”, arriving with Major Peter VanAlstine’s group of loyalists in 1784. He was given a grant of land on what is still known today as Trumpour’s Point. Paul had been an ensign or “cornet” in DeLancey’s Brigade during the Revolutionary War, and evacuated from New York as an “Associated Loyalist”1

He is known from Mrs. Simcoe’s Diary, where she refers to a visit she paid him:

“March 11, 1795…We set out at 11:00 and drove 14 miles to Trumpour’s Point, so named from a man who lives there. He was formerly in the 16th Dragoons, and lives by selling horses. His wife gave me some good Dutch cakes, as I could not wait to eat the chickens she was roasting in a kettle without water. This house commands a fine view.”2

Paul was back in the saddle again – literally – during the War of 1812, as the captain of a company of militia – the 1st Lennox – that was referred to as “Trumpour’s Dragoons”, his son John as his second in command with the rank of Lieutenant. When Captain Paul died on 27 March 1813, his son was promoted and took over command of the company.3

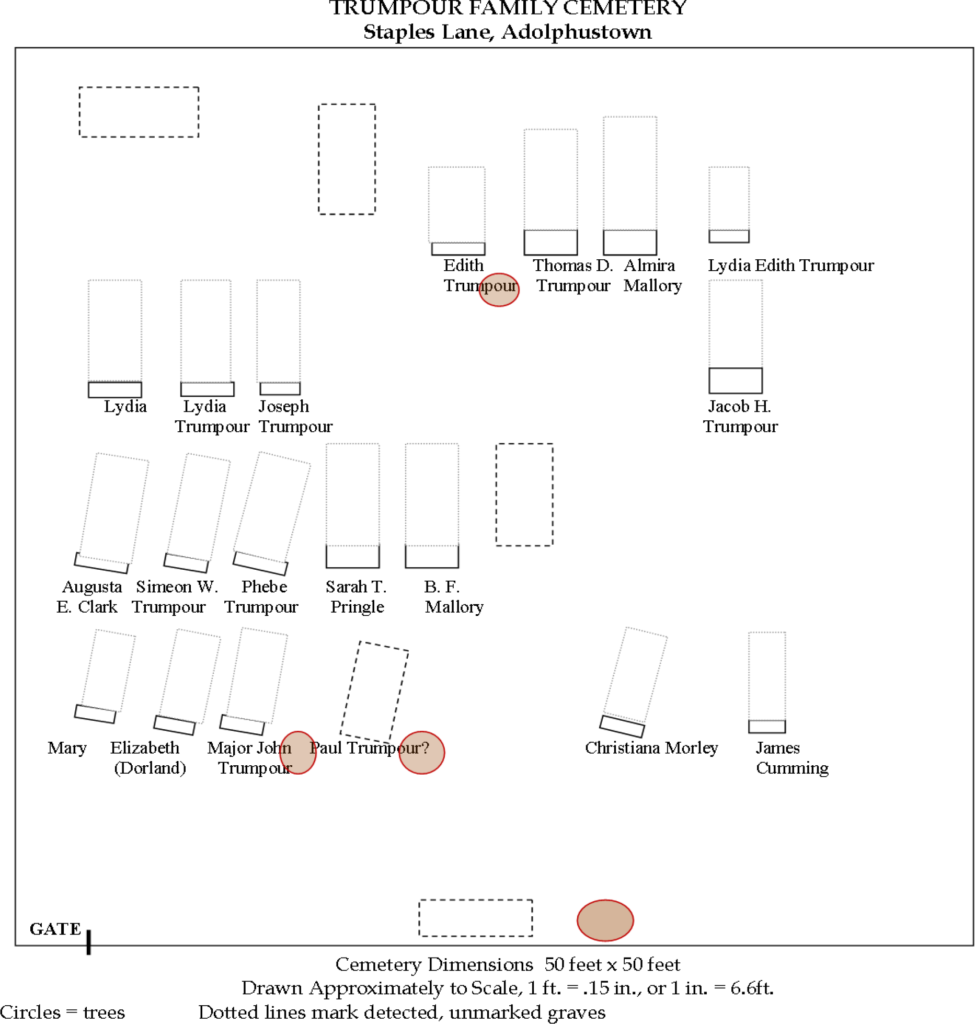

On Trumpour’s Point sits the family cemetery where several of his children, their children and the children’s children were all buried, including Major John Trumpour. Curiously, however, there is no grave marker for Paul himself.

On Trumpour’s Point sits the family cemetery where several of his children, their children and the children’s children were all buried, including Major John Trumpour. Curiously, however, there is no grave marker for Paul himself.

My family and I began to visit the little, deserted cemetery (the last burial there is dated 1906) when I was young. I recall the first time finding it hopelessly overgrown, and having to return with a scythe and armed with spray to kill the poison ivy. We made a point of returning periodically over the years to try and tend to the cemetery, in a small way, by cutting the grass and clearing the overgrowth. We also recorded all the tombstones. At length, the former Adolphustown Township assumed responsibility, thanks to the grave of a veteran of the War of 1812, Major John Trumpour. The care for the cemetery included grass cutting placing a sign at the end of Staples’ Lane, cheerfully used for target practice by duck hunters.

One feature of the cemetery that draws attention is that the first burial is that of “James Cumming, Esq., a Native of Scotland” in 1817. No further grave markers appear until Major John’s in 1846. The obvious question is, “Why would James Cumming be buried there in 1817, unless it was already marked as a family burial ground?” James was the husband of Paul Trumpour’s daughter, Christiana, so it would explain his presence, but why would he be the first? Perhaps he was not the first. Perhaps there actually was a burial there already, namely that of Captain Paul himself? As can be seen from the accompanying diagram, there are a lot of empty areas in the cemetery. Was Paul to be found somewhere in one of those? And if so, why did he have no grave marker?

My hypothesis for many years has been that since Paul died during the War of 1812, and early in it at that, there may have been material shortages, in particular of stone which would have been needed for fortifications, and also of the people to fashion it. Moreover, at the time of Paul’s death, Upper Canada had been in existence for less than 30 years and there was little in the way of infrastructure, including stone quarries (the Queenston quarry of Niagara was established in 1837), so it seems likely that Paul’s grave marker would have been made of wood, and long since rotted away. The nearby Hay Bay Church is surrounded by numerous early burials, none of them marked, for this very reason.

Bill Cowan is an avid historian, particularly interested in family and local history. I was delighted when he agreed to accompany me on a visit to the cemetery, as it is one he had not seen before. He shared my dismay at seeing the dilapidated condition of the grave monuments. Two had sunken so far into the ground that the tilt had toppled the upper portions onto the ground beside them. Another lay flat on the ground on its back, and was filled with water. Others were broken off and prone. We vowed to return and attempt some minor restoration. In addition, Bill suggested we bring along his metal detector, in an attempt to see if we could identify other gravesites in the open areas of the cemetery, reasoning that even old coffins would have needed metal reinforcing at the corners, handles at the ends, and so forth.

Bill Cowan is an avid historian, particularly interested in family and local history. I was delighted when he agreed to accompany me on a visit to the cemetery, as it is one he had not seen before. He shared my dismay at seeing the dilapidated condition of the grave monuments. Two had sunken so far into the ground that the tilt had toppled the upper portions onto the ground beside them. Another lay flat on the ground on its back, and was filled with water. Others were broken off and prone. We vowed to return and attempt some minor restoration. In addition, Bill suggested we bring along his metal detector, in an attempt to see if we could identify other gravesites in the open areas of the cemetery, reasoning that even old coffins would have needed metal reinforcing at the corners, handles at the ends, and so forth.

Return we did. Our targeted grave markers were leveled and re-erected, and we tested the theory that a metal detector might be successfully used to identify unmarked burials.

Return we did. Our targeted grave markers were leveled and re-erected, and we tested the theory that a metal detector might be successfully used to identify unmarked burials.

[at right: Bill Cowan and metal detector, standing on the location where we believe Capt. Paul Trumpour was buried.]

The technique was to place a simple garden stake at points where the detector indicated iron. Right away, the stakes gave us a rectangle measuring 60” by 20”. Just to be sure, we moved to one of the marked graves, and sure enough, the detector showed iron at the places expected. So we continued, and over the course of about a half hour identified four more graves where there was no visible marker. Interestingly, one of those was within a foot of where, years ago, I had conjectured we might find Captain Paul.

So who are all these new graves, more than I had ever imagined? One might possibly be Paul’s wife, Deborah (née Emery). According to a report in the Upper Canada Herald dated September 25, 1827, she died on 20 September of that year (in her 69th year) in Hallowell, Prince Edward County. Why she would have been in Hallowell, I do not know. But no online cemetery record in either Prince Edward County or South Fredericksburg has a record of her, so it is entirely possible that her body may have been returned to Adolphustown and Trumpour’s Point for its final resting place.

Who else might be buried there? Well, since the Paul Trumpour household numbered 17 in 1806, according to one record, there are lots of candidates. Not all 17 were immediate family. Paul and Deborah had 7 children, so presumably some of the other eight were hired hands; four (I am going by memory on the number) were slaves. All these would be possible candidates for occupants of the newly identified graves.

If anyone has an interest in undertaking activities in an ancestral cemetery, we would recommend you make contact with the Adolphustown Fredericksburgh Heritage Society (sfredheritage.on.ca), as there are many potential pitfalls. Susan Walker and Jane Lovell of the Society are very helpful and knowledgeable community resources, and can help you navigate. A huge thanks to them.

[Ovals indicate tombstones restored and/or straightened as of 24-10-19]

[Ovals indicate tombstones restored and/or straightened as of 24-10-19]

Footnotes:

1 See Larry Turner, Voyage of a Different Kind: The Associated Loyalists of Kingston and Adolphustown, 1984, Mika Publishing, Belleville

2 Mary Quayle Innes (Ed.), Mrs. Simcoe’s Diary, 1971, Macmillan, Toronto, 154

3 William Gray, Soldiers of the King: The Upper Canada Militia, 1812-1815, 1995, Boston Mills Press, Erin Ontario, 165