The History of Slavery Along the St. Lawrence River

(a talk by Jennifer DeBruin)

May 30, 2018

Jennifer DeBruin’s topic was “The History of Slavery Along the St. Lawrence River”.

Jennifer began by saying that for many years, like most Canadians, she assumed that slavery involved only the southern United States, until she discovered that some of her ancestors held slaves in the province of New York, prior to the American Revolution.

Jennifer began to research the issue of slavery, and discovered that a total of 36,000 ship crossings of the Atlantic carried enslaved Africans to North and South America during the period the slave trade existed. She mentioned an animated video at slate.com that illustrates the numbers of ships transporting slaves, year by year.(https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2021/09/atlantic-slave-trade-history-animated-interactive.html). The anti-slavery movement also began much earlier than we might think, in the early 1700s.

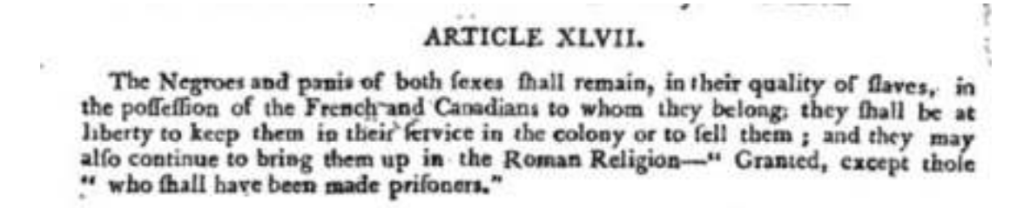

In Canada, enslaved people first were brought to Quebec in the 1600s, to provide manpower as the colony expanded. About 4,500 enslaved individuals appear in Quebec records, often with only one name given, and often referred to as “domestique”. After Britain conquered Quebec, the Capitulation Agreement of 1760 contained Article 47 which specifically guaranteed that “Negroes and panis [indigenous]” were still the property of their “owners”.

Article 47, Articles of Capitulation. From A collection of the acts passed in the Parliament of Great Britain and of other public acts relative to Canada (Quebec: P.E. Desbarats, 1824), p. 22; online at EarlyCanadiana.ca

Article 47, Articles of Capitulation. From A collection of the acts passed in the Parliament of Great Britain and of other public acts relative to Canada (Quebec: P.E. Desbarats, 1824), p. 22; online at EarlyCanadiana.ca

Sir John Johnson, revered by Loyalist descendants as an important leader before and during the American Revolution, brought 14 enslaved persons with him when he moved to Montreal. His late father, Sir William Johnson – whose consort Molly Brant was a leader among the Mohawks of New York Province and later in Upper Canada, particularly the Kingston area – owned 30 slaves at the time of his death in 1774. Quite apart from the free blacks who came to Nova Scotia as Loyalists and were grudgingly given land by the British (albeit not as much as white Loyalists), Jennifer told us that there were approximately 3,000 slaves brought to Canada by Loyalist owners, including 500-700 brought to Upper Canada. Jennifer mentioned a document from 1783 that included Negroes among the list of chattels which could be imported into Canada duty-free.

In the first Parliament of Upper Canada, 1792-96, 6 of the 16 members of the lower house owned slaves; an even higher percentage of the upper house did so, and Peter Russell the attorney-general was a slave owner. Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe attempted to get them to outlaw slavery, but the best he could accomplish was getting them to pass on July 9, 1793, The Act To Limit Slavery which banned the importation of slaves and mandated that children born henceforth to female slaves would be freed upon reaching the age of 25. Members of the second Parliament were even more committed to maintaining slavery, since 14 of 17 members were from slave-owning families.

In Kingston area, it is well known that William Fairfield, whose home on Bath Road is visited annually by many tourists, had several slaves.

Despite the 1793 act, the last sale in Upper Canada was that of a 15-year-old boy sold in 1824.

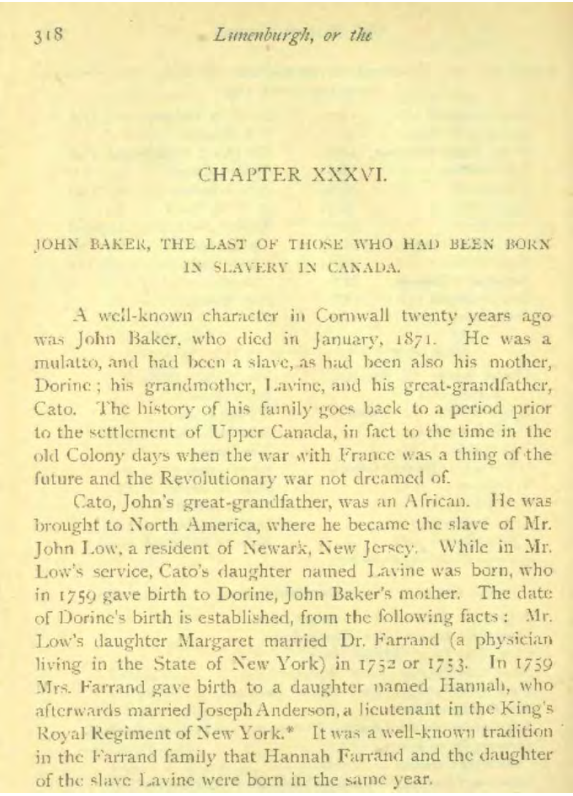

Jennifer also spoke of John Baker, the last person born into slavery in Canada. His story is told in the 1890 book Lunenburgh and the Old Eastern District, now available as a historical reprint and also online at https://archive.org/stream/lunenburgh00prinuoft/lunenburgh00prinuoft_djvu.txt (or you can choose “Other format” on that page and download the book as a PDF file).

Chapter XXXVI states that when John Baker died in Cornwall, Ontario on 18 January 1871, some people believed that he was 104 or 105 years of age but the author explains, based on several facts of Baker’s life, he was probably 93.

Chapter XXXVI states that when John Baker died in Cornwall, Ontario on 18 January 1871, some people believed that he was 104 or 105 years of age but the author explains, based on several facts of Baker’s life, he was probably 93.

Canada also played a major role in the escape of slaves from the United States via the Underground Railway, particularly after the passing of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850. While we usually hear of former slaves (such as Josiah Henson, who may have served as inspiration for Uncle Tom in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin) crossing at Detroit and settling in the area between Windsor and London, Jennifer illustrated the Champlain Route, bringing former slaves north through New York state. Many crossed at Ogdensburg where the St. Lawrence was narrowest and it was easy to row a boat across to freedom. Many of those crossing in eastern Ontario did then make their way to the Essex County area to rejoin family and friends; others may have gone to Quebec.

This was an extremely educational talk and those present came away with a new awareness. Perhaps we’ll examine our own Loyalist ancestors’ lists of “chattels” more closely, if we can find them.