The Loyalists of Ernestown 1786

(a talk by Richard Parry)

March 27, 2021

We were privileged to see an excellent presentation by our Branch Historian, Richard Parry, on “The Loyalists of Ernestown 1786”.

Richard told us that the project began in early spring of 2019 as plans were being prepared for Kingston and District Branch’s participation in the Canada Day celebrations in Bath. We were to have a booth in the park where branch members could spend the day interacting with the hundreds of visitors: Bath has long been known for its major parade as well as other activities on July 1, Canada Day.

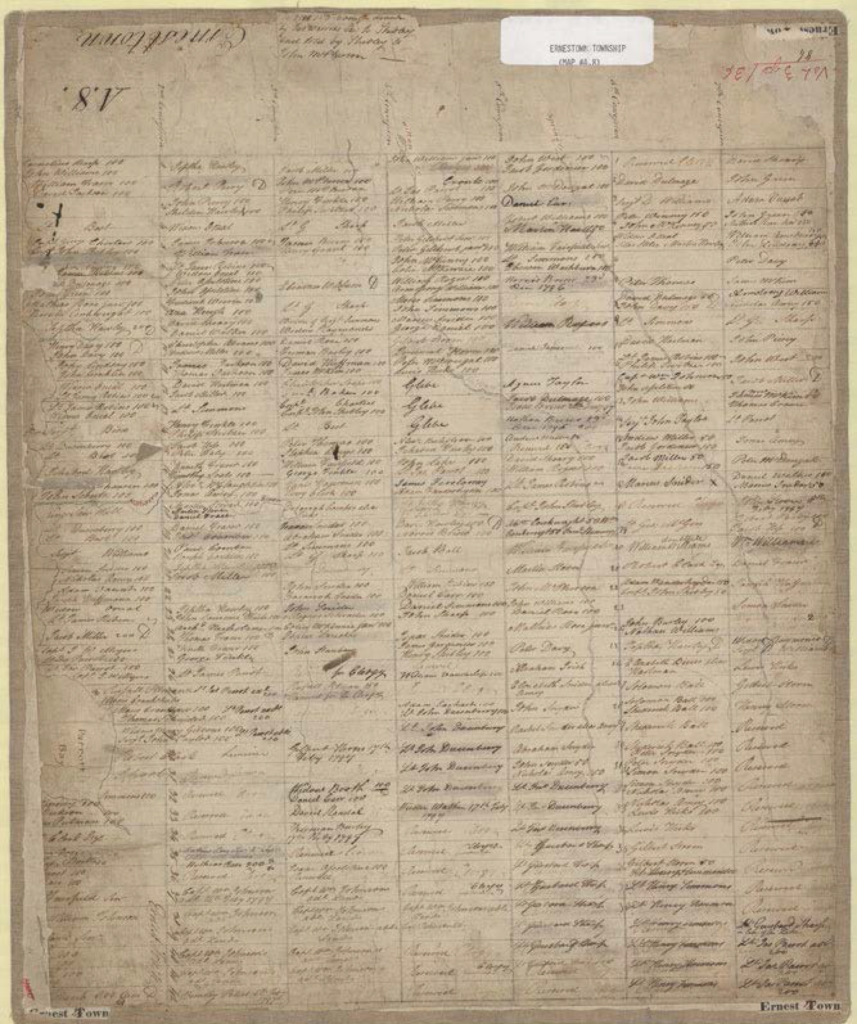

Genealogist Anne Redish suggested to Richard that we should have some focal point for discussions with attendees and wondered if a map would be a good idea. They settled on a map showing land patents from 1783: the names of men assigned to 294 lots surveyed in the township, giving Lot Number, Concession Number and Number of Acres assigned to each. (Of the 294 lots, 26 were reserved for the Crown and 3 for Glebe land, i.e. for churches.)

As United Empire Loyalists were being assigned new homes in which to settle, the British government – represented by Governor Haldimand – decided to keep disbanded regiments together, for several reasons. The men would be among fellow soldiers they already knew and had worked with, so there would be good cooperation when help was needed. Land assigned to officers was scattered throughout the township in the belief that would help preserve discipline among the settlers. And, if hostilities broke out again, the regiment would be easily re-assembled to return to duty.

Thus, Ernesttown Township (as it was first known, since it was named for King George III’s fourth son, Prince Ernest Augustus: the second “t” eventually disappeared) was assigned to officers and men of Jessup’s Rangers. It seems that the patent map was drawn up while they were still in Quebec over the winter of 1783-84, before they undertook the arduous trek west to Lake Ontario.

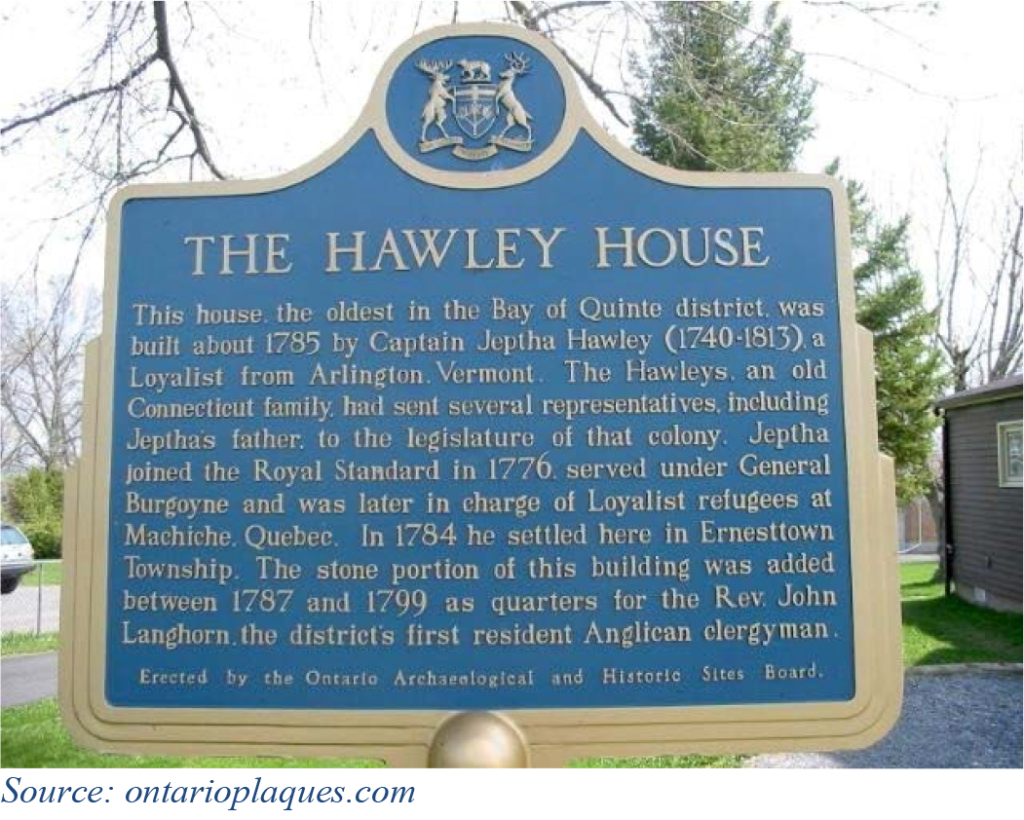

Richard reported that very little information exists about the movement of the Loyalists westward up the St. Lawrence River from Quebec. He did manage to find documentation that Jephtha Hawley was put in charge of the settlers waiting at Machiche, Quebec. (Jephtha Hawley’s home is the oldest existing building in the village of Bath – the former village of Ernestown – and is a designated historical site.) Hawley drew up destination lists: some Loyalists were to travel east to Chaleur Bay in what would become New Brunswick, others to Cataraqui, Adolphustown or Ernesttown in what would become Upper Canada.

Richard reported that very little information exists about the movement of the Loyalists westward up the St. Lawrence River from Quebec. He did manage to find documentation that Jephtha Hawley was put in charge of the settlers waiting at Machiche, Quebec. (Jephtha Hawley’s home is the oldest existing building in the village of Bath – the former village of Ernestown – and is a designated historical site.) Hawley drew up destination lists: some Loyalists were to travel east to Chaleur Bay in what would become New Brunswick, others to Cataraqui, Adolphustown or Ernesttown in what would become Upper Canada.

At first Haldimand decreed in November 1783 that lands were to be distributed as Seigneury lots, in the manner that land was already held in Quebec. This would have meant that settlers could not own their land and would have to pay rent. The Loyalists were angered and sent a petition to Haldimand, who countermanded the order and said that land was to be given free to Loyalists.

Between December 1783 and January 1784 the members of Jessups’ corp were discharged. Haldimand had ordered the building of bateaux in Lachine, Quebec. These were flat-bottomed, double-ended boats [that is, a point at each end] that were about 36 to 45 feet in length and were good for carrying cargo. Some Durham boats were used as well, which were slightly longer. Groups departed Machiche between late spring and early fall. Haldimand paid for a guide for each flotilla. Richard found records for one group, guided by Baron de Reitzenstein, which consisted of 218 individuals: 45 men, 35 women, 68 boys and 70 girls. They departed on 31 May 1784. When they reached Montreal, they discovered that their tents were not ready, so had to stay there until 15 June. (Loyalists were issued one tent per 5 people; the tents were to be returned to the government after they had built a cabin. One wonders how many tents were actually returned, when the canvas could obviously be used for many purposes around the property?) Other supplies provided by the British government included:

Each man and boy over the age of 10 years was to be given a coat, waist coat, breeches, hat, shirt, blanket and shoe soles.

Each woman and girl over the age of 10 years was to be given two yards of woolen cloth, four yards of linen, stockings, a blanket and shoe soles.

They were also issued some tools such as axes, which may have been shared between a couple of families.

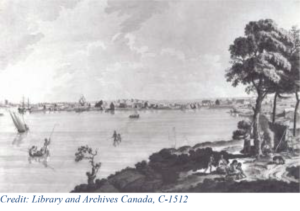

Richard found at Library and Archives Canada a painting by James Peachey showing what Kingston would have looked like as the Loyalists reached it and passed it. Peachey was a former army officer and assistant to Samuel Holland, Surveyor General. His watercolour paintings include “A view of Cataraqui from Captain Brant’s House, July 16, 1784”. The date may not exactly correspond to when Baron de Reitzenstein’s flotilla passed Kingston, but the timing may well have been close. It would not be a quick journey: every time the boats reached rapids (e.g. at Lachine or Long Sault), they would have had to empty the bateaux, haul the boats up the rapids with ropes, then carry all the goods along the shore to a point where they could re-load them into the bateaux and continue on. It would certainly have taken several men and an additional number of boys to pull each boat past the rapids. The entire process would probably have involved an all-day effort for each barrier in the river.

Richard found at Library and Archives Canada a painting by James Peachey showing what Kingston would have looked like as the Loyalists reached it and passed it. Peachey was a former army officer and assistant to Samuel Holland, Surveyor General. His watercolour paintings include “A view of Cataraqui from Captain Brant’s House, July 16, 1784”. The date may not exactly correspond to when Baron de Reitzenstein’s flotilla passed Kingston, but the timing may well have been close. It would not be a quick journey: every time the boats reached rapids (e.g. at Lachine or Long Sault), they would have had to empty the bateaux, haul the boats up the rapids with ropes, then carry all the goods along the shore to a point where they could re-load them into the bateaux and continue on. It would certainly have taken several men and an additional number of boys to pull each boat past the rapids. The entire process would probably have involved an all-day effort for each barrier in the river.

Back to Richard’s 2019 project… to obtain information on every Loyalist named on the Ernesttown Patent map. He wanted to be able to look up land and people quickly when someone came to the branch’s booth, so after filling binders with more detailed information on each man named on the map, he generated two indexes: one organized by Surname, linking the name to the Lot and Concession; and one by Concession/Lot number, referring to Surname. He spoke with many visitors to the booth that day, some descended from Loyalists who were delighted to find their surname in his binders, others who wondered who had first been given the lot on which they now live. Since that time, Richard has placed four copies of these binders at locations accessible to members of the public: Kingston Frontenac Public Library (Central Branch), Lennox & Addington County Museum and Archives, the Bath Museum, and the Loyalist Research Centre at Adolphustown.

Back to Richard’s 2019 project… to obtain information on every Loyalist named on the Ernesttown Patent map. He wanted to be able to look up land and people quickly when someone came to the branch’s booth, so after filling binders with more detailed information on each man named on the map, he generated two indexes: one organized by Surname, linking the name to the Lot and Concession; and one by Concession/Lot number, referring to Surname. He spoke with many visitors to the booth that day, some descended from Loyalists who were delighted to find their surname in his binders, others who wondered who had first been given the lot on which they now live. Since that time, Richard has placed four copies of these binders at locations accessible to members of the public: Kingston Frontenac Public Library (Central Branch), Lennox & Addington County Museum and Archives, the Bath Museum, and the Loyalist Research Centre at Adolphustown.

One fact Richard discovered is that many of Jessup’s men apparently never set foot on the land assigned to them on the map. They were likely issued their land “tickets” while in Machiche, and probably traded them with others so that, for example, two brothers could have adjacent properties instead of being separated by three concessions. Others may have reached the land assigned to them, realized it was not good for farming, and sold or traded the ticket, moving on to another community. This caused confusion when the Upper Canada Land Board was finally convened (1789) because the master list did not match the actual land occupancy: hence the need for the Heir and Devisee commissions to sort matters out.

With his research project completed, Richard turned to the question of where the Ernestown and other Loyalists were buried. Almost all the cemeteries in Lennox & Addington and Frontenac Counties have long since been transcribed and published by the Kingston Branch of the Ontario Genealogical Society, and the Quinte Branch OGS have done the same for cemeteries in Prince Edward and Hastings Counties. However, surprisingly few headstones actually mention the fact that the person was a UEL.

Richard spent his 2020 pandemic summer driving to cemeteries in the four counties mentioned and photographing stones. He uploaded over 4,000 memorials to FindaGrave.com as well as 11,000 photographs. Using the UELAC Loyalist Directory, his Ernestown binder and other reference materials, he could indicate which people were UELs. He has also collected information on which graves belong to War of 1812 veterans as well and has turned the data over to the appropriate body who is willing to commemorate each group.

For the War of 1812 participants, their graves will eventually be marked by the War of 1812 Graveside Project – see https://gravesideproject.ca/ for further information. For Loyalists, markers in this area may be placed by members of the Canadian Fencibles, a re-enactor regiment. The project has been spearheaded by David Smith UE. Plans for marking ceremonies, of course, are all on hold until after the pandemic.

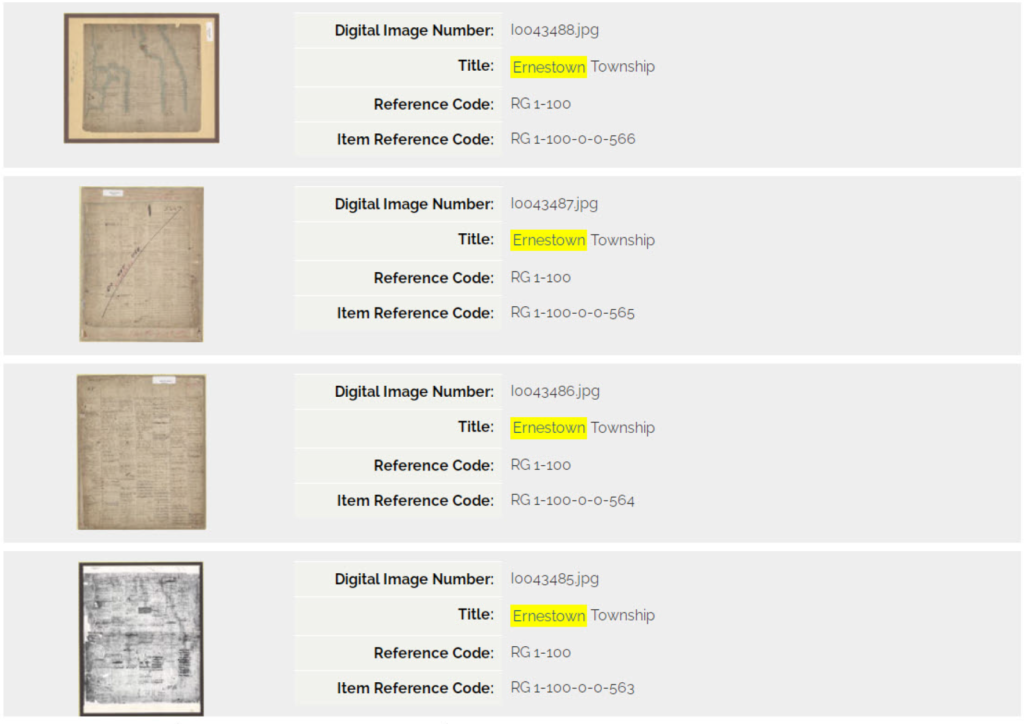

To find a Patent Map for anywhere in Ontario, go to http://www.archives.gov.on.ca/en/about/patent-plans.aspx. Richard found his map from that page by entering “Ernestown” as a keyword in the Archives of Ontario Visual Database search box. The result was:

A quick glance suggests the third map is the clearest.

Digital map from Archives of Ontario, Reference RG1-100-0-0-564. Ernestown Township.

Digital map from Archives of Ontario, Reference RG1-100-0-0-564. Ernestown Township.