The Many Layers of the Lower Burial Ground,

St. Paul’s Churchyard and under the Church Hall, Kingston Ontario

(a talk by Sue Bazely)

November 28, 2020 – Newsletter Issue #1 (2021)

Sue began by outlining the history of the Kingston area. The Haudenosaunee moved through the area on a seasonal basis about 1000 to 1500 years ago, following the migrations of animals. About 1450 they settled a small village on the banks of the Little Cataraqui River.

In 1673 the first Europeans arrived, when the French built a fur trading post and named it Fort Frontenac. There were actually three versions of the French fort, each larger and stronger than its predecessor.

As white settlers grew in number under both French and English rule, their beliefs and religious practices made it necessary to open burial grounds. In 1783 the Lower Burial Ground (then without the adjective “Lower”) was laid out as the Loyalists arrived. It was used for interring Kingstonians of all denominations until 1808 when St. Columba Cemetery was opened for burial of Roman Catholics. (The Heritage Cemetery at Cataraqui, located next to Cataraqui United Church on Sydenham Road, opened about the same time but was of course far beyond the confines of the town of Kingston.)

When the Upper Burial Ground (now McBurney Park) was opened in 1825, residents had to begin referring to this one as the Lower Burial Ground in order to differentiate them. And in 1827 the Union cemetery was opened, for those of non-conformist denominations (now under Bethel Church on Johnson Street).

St. Paul’s Church was erected in 1847 – smack in the middle of the Lower Burial Ground. Little consideration was given to the fact that the walls were rising over top of some graves.

In 1854, after a fire, they enlarged the north end of the church. In 1872 the Sunday School was constructed, now part of the church hall where our branch has been meeting. Again, there would have been earlier grave markers on that land to the west and north of the initial church.

In 1931, water and sewer services were added, and again that digging must have disturbed at least some early graves.

In 1937, church member Charles Long wrote up a history of the church and transcribed some burial records. He mentioned “71 memorials under the parish hall.”

In 1959-60 an addition joined the Sunday School building to the church. In 1970 the land to the east and north of the church building was paved over for parking.

The Lower Burial Ground Restoration Society was formed in 2008. This volunteer group has overseen such things as rebuilding of the western wall of the churchyard along Montreal Street, after a car crashed into it and took down a portion of the stone wall. They have completed several projects to restore particular graves such as the Forsyth Monument and the Stuart Lair.

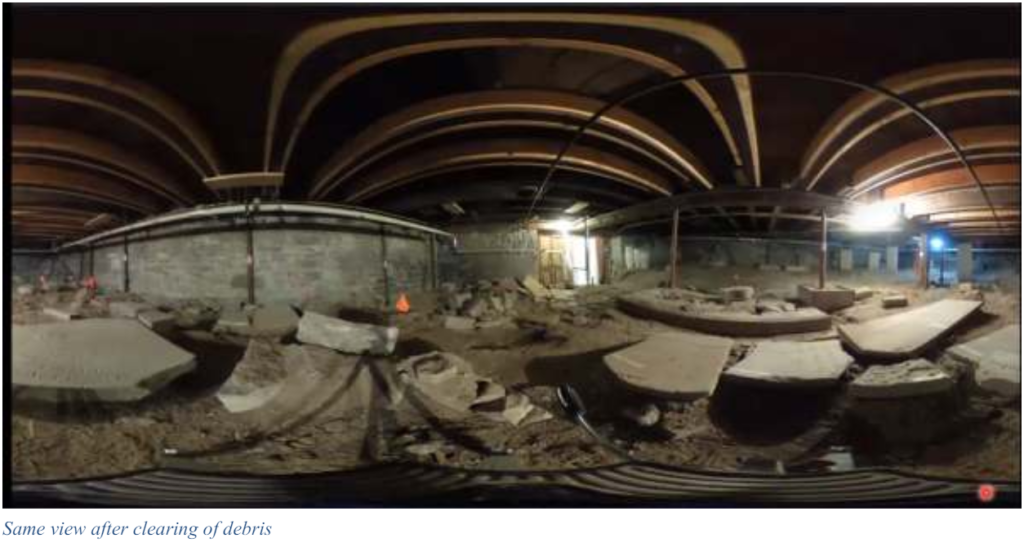

The current project of the LBGRS is the “Cultural Resources Inventory Project”. Stage 1 involves archaeological assessment. During the summer of 2019, archaeologist Sue Bazely led a team of volunteers, working in cooperation with some technical staff and in difficult working conditions such as low headroom and dust, to clear out all the debris that covered many stones and pieces of stones under the church hall. They were not permitted to actually dig or lay out a grid, as is the normal practice for archaeological explorations. Instead, they slowly and painstakingly brushed off the dust and debris which had accumulated over the gravestones since the hall was erected in 1872.

Since the team could not drive in spikes for a grid, they had to settle for anchoring 8 screws in the foundation walls and running strings between them, with some little flags to mark positions. Sue had wanted to use GPS to establish reference points but could not acquire the satellites from this underground position. Instead, they made use of City of Kingston engineering data drawn up by surveyors over time so they could establish elevations. Two professional surveyors kindly donated their time and expertise to work out, from known location points outside of the churchyard, at what elevation the areas under the church hall and church were located.

Since the team could not drive in spikes for a grid, they had to settle for anchoring 8 screws in the foundation walls and running strings between them, with some little flags to mark positions. Sue had wanted to use GPS to establish reference points but could not acquire the satellites from this underground position. Instead, they made use of City of Kingston engineering data drawn up by surveyors over time so they could establish elevations. Two professional surveyors kindly donated their time and expertise to work out, from known location points outside of the churchyard, at what elevation the areas under the church hall and church were located.

Working conditions

Working conditions

Sue had planned to record features they uncovered using apps on her phone, but there was too much dust in the air to risk using the phones, so they had to resort to old fashioned methods: paper and pencil. Sue had to teach the graduate students, who were well versed in 21st century technology, how to use tape measures and plumb bobs to note the measurements.

Anne Redish’s husband Adair later entered their data into a computer aided design program (CAD) so the careful mapping could be printed out. They were able to work with faculty and students from Queen’s University who used a terrestrial laser scanner using LIDAR to get a spatially comprehensive scan of the crawl space under the church hall. Sue was able to show us a 3D image of the site.

Another 21st-century technology that the team were able to use is Ground Penetrating Radar, used in the churchyard to detect where there may be burials with no markers. GPR looks for subsurface disturbances. They were also able to use this at one end of the basement, and found some anomalies which need to be studied in more detail: they could represent burials or else naturally occurring boulders.

Right: Getting the GPR machine into the small entry to the space was a major accomplishment.

Right: Getting the GPR machine into the small entry to the space was a major accomplishment.

All photos in this story were obtained from screen shots from the Zoom meeting, with gracious permission of Sue Bazely.

A third technique, Reflective Transformation Imaging, was demonstrated to our branch some years ago at a meeting. Its use on gravestones above ground is well described with accompanying photos on the website of the Lower Burial Ground Restoration Society, https://www.lowerburialground.ca/conservation/. While tripods and tall lights could not be used under the church hall, trouble lights with incandescent lightbulbs held beside stones at different angles made it possible to bring out details that were otherwise impossible to read.

The photo on the next page is of the tombstone of William Atkinson. A sister of William married Robert Graham. Both William Atkinson and Robert Graham came with Michael Grass and other members of the Company of Adventurers who arrived in Kingston in 1783. It’s believed that William Atkinson’s wife was named Eliza. These facts were provided by Joan Lucas UE, longtime and recently retired Branch Genealogist for Kawartha Branch, and a distant relative of William Atkinson.

The stone, which was found lying under the rubble that was cleared, reads “William Atkinson of Kilburn in Yorkshire died the 7th April 1805 aged 54 yr 9 mo and 4 dy.”

Sue calculated that volunteers contributed 795 hours to the project during the summer of 2019. They had, of course, planned to continue the project during the summer of 2020, until Covid-19 intervened. Still, she was proud to say that they had already transformed a nineteenth-century garbage dump back to a sacred landscape.

Sue calculated that volunteers contributed 795 hours to the project during the summer of 2019. They had, of course, planned to continue the project during the summer of 2020, until Covid-19 intervened. Still, she was proud to say that they had already transformed a nineteenth-century garbage dump back to a sacred landscape.

Among the debris they removed were several Bibles and a 1903 sex manual. There were loose pieces of headstones and footstones, including 20 fragments recovered from the furnace room under the church. All dust was carefully screened for any human remains, and the small fragments of bone that were recovered will be re-buried on the site. In response to a question, Sue stated that it is impossible to know how many burials in the Lower Burial Ground have been disturbed over time by the various construction operations. At least they have restored dignity to a small portion of it.

And no, they did not find the grave of Molly Brant!