“Whereas it is Unjust” – Upper Canada’s Role in the Fight to End Slavery

(a talk by Jean Rae Baxter)

September 25, 2021

At our September meeting, award-winning author – and our own Programme Chair – Jean Rae Baxter spoke on “WHEREAS it is Unjust” – Upper Canada’s Role in the Fight to End Slavery.

Jean began by stating that today we acknowledge that some Loyalists were slave owners. This was not unusual at the time, or even much earlier in history. What became Upper Canada was part of Quebec, where slavery had existed from the 1600s among the French and much earlier among Indigenous nations themselves. Slaves there included both Indigenous captives, termed “Panis” [a corruption of the word Pawnee], and black slaves imported from New England. Blacks came to be preferred in Quebec, because the Panis more frequently ran away into the woods and could use their considerable skills to survive there: Blacks imported from the provinces to the south were less likely to escape.

Slave owners both north and south of the new border believed that slavery was just a part of life: it made their lives easier, it was necessary for the economy, and not even the Bible said anything to condemn it. After all, St. Paul wrote “Slaves, obey your masters.”

When the British conquered New France, the Articles of Capitulation signed at Montreal on 8 September 1760 included a specific clause on enslavement:

The Negroes and panis of both sexes shall remain in their quality of slaves, in the possession of the French and Canadians to whom they belong; they shall be at liberty to keep them in their service in the colony, or to sell them; and they may also continue to bring them up in the Roman Religion.

The clause made it very clear, said Jean, that slavery was legal under British rule.

Many of those present at the meeting were surprised to hear Jean say, “Twelve years later, in 1772, slavery ended in England. … The end of slavery in England resulted from a legal judgment in a case called the Somersett Case.” Abolitionists had brought suit on behalf of James Somersett, a slave who escaped from his owner, was recaptured, and was about to be sent to a plantation in Jamaica by his owner. Jean summarized the 1772 ruling in the Court of King’s Bench by Lord Mansfield, that since neither Common Law nor Statute Law nor Natural Law supported the institution of slavery, “the man must be discharged.”

No person could henceforth be a slave in England, but the judgment had no effect on slavery in British North America. It was not until 1834 that slavery was actually abolished throughout the British Empire.

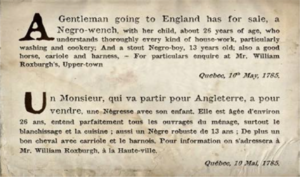

Jean showed this advertisement from a Quebec City newspaper and pointed out that the gentleman would have had to free his slaves once they arrived in England. Evidently he preferred to sell them prior to his departure.

Jean showed this advertisement from a Quebec City newspaper and pointed out that the gentleman would have had to free his slaves once they arrived in England. Evidently he preferred to sell them prior to his departure.

Advertisement found at https://www.historymuseum.ca/virtualmuseum-of-new-france/

As Loyalists flooded north after the American Revolution, the issue that concerned them was not could they bring their slaves – that was a given – but could they bring them without paying duty?

The Imperial Statute of 1790 expressly allowed immigrants from the United States to bring in “negros [sic], household furniture, utensils of husbandry, or cloathing [sic]” duty free.

Jean found estimates that by 1792, there were about 2,000 slaves in the Maritimes, 300 in Lower Canada and 500-700 in Upper Canada. Among notable Loyalists, the Deputy Superintendent of the Indian Department, Matthew Elliott, owned at least 60 slaves. Sir John Johnson and Rev. John Stuart brought slaves with them; Joseph Brant owned 45. Even Molly Brant had three slaves.

Jean cited a couple of events in Simcoe’s history showing that he was already against slavery and prejudice. She quoted a letter (found in the Simcoe Papers) stating: “From the moment that I assume the government of Upper Canada, under no modification will I assent to a law that discriminates by dishonest policy between the natives of Africa, America or Europe.” (Collection of the Nova Scotia Historical Society for the years 1896-98, Vol X. Halifax, N. S. Nova Scotia Printing Company 1899.)

Jean cited a couple of events in Simcoe’s history showing that he was already against slavery and prejudice. She quoted a letter (found in the Simcoe Papers) stating: “From the moment that I assume the government of Upper Canada, under no modification will I assent to a law that discriminates by dishonest policy between the natives of Africa, America or Europe.” (Collection of the Nova Scotia Historical Society for the years 1896-98, Vol X. Halifax, N. S. Nova Scotia Printing Company 1899.)

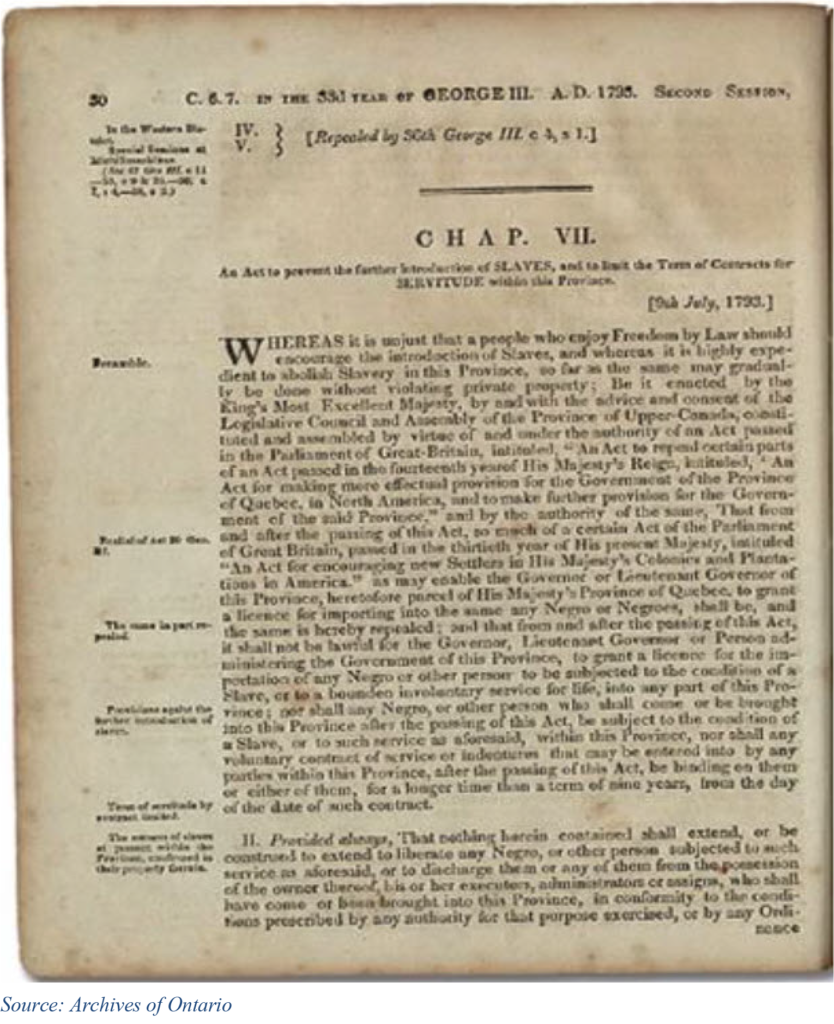

Thus, during the second session of the first parliament of Upper Canada, which met at Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake) on May 31, 1793, Simcoe instructed the Attorney General to introduce a bill to “prevent the further introduction of slaves” and to “limit the terms of contracts for servitude within the Province.” It would now be illegal to import slaves. Existing slaves would remain the property of their owners, but any children born after the Act was passed would not be slaves. They were entitled to remain with their mothers, supported by the masters, “until such child shall have obtained the age of twenty-five years, at which time such child shall be entitled to demand his or her discharge from, and shall be discharged by such master or mistress from any further service.” Owners were required to register the births of such children in order to facilitate this.

Clearly this was not a popular proposition: if the owner wished to keep his existing slaves, he had to feed and clothe their children for up to 25 years and then watch them walk away. There was much opposition expressed when the bill was discussed, but it did successfully pass both the House of

Assembly, where slave owners were in the minority – 6 out of 16 members – and the Legislative Council, where it passed unanimously despite the fact that 6 out of 9 members owned slaves.

This Act did not free any slaves, but as Jean quoted Simcoe, “the enslaved persons now had the satisfaction of looking forward to their descendants being free.”

Jean also discussed how Free Blacks were treated. Some received the same land and supplies as did disbanded white soldiers. One, a former slave named Richard Pierpoint who had escaped from his master and served with Butler’s Rangers during the Revolution, petitioned Simcoe for land to establish an all-black community. Simcoe refused to accept the petition, since the idea of segregated communities went against his belief. (Pierpoint presented another petition to the government in 1812 after war broke out, to create an all-Black militia to fight for the British. This petition was successful. “Captain Robert Runchey’s Corps of Coloured Men” served in many battles, including the Battle of Queenston Heights and the Battle of Stoney Creek. Jean commented wryly that Captain Runchey was of course white.)

Simcoe left Upper Canada in 1798 due to ill health. In his absence, Christopher Robinson tried to partly reverse the Act of July 1793, so that new immigrants coming from the USA or the Caribbean to settle could bring their slaves. It passed in the House of Assembly, but Richard Cartwright of Kingston, despite being a slave-owner himself, stalled the bill in the Legislative Council until it died at the end of the session.

The last recorded sale of a slave in Upper Canada took place in Thurlow, Hastings County, in March 1824. By the time slavery was abolished throughout the British Empire in 1834, there were probably no more than 50 people left enslaved in Upper Canada.

Jean gave a very interesting and informative presentation. I for one look forward to her book which is now supposed to be published on November 30, 2021. It can be pre-ordered right now from Amazon, and no doubt will be available from local booksellers after that date.

[Transcription by Nancy Cutway]